The opening presentation of this year's annual Board Retreat was that of the Board's Audit & Accountability Committee.

The Board established the Audit & Accountability Committee in the Fall of 2008, during the period leading up to the vote on the 6.9 mill Permanent Operating Levy, which was passed in November 2008. The members of the Committee were named in February 2009, and they have been working very intently on their assigned mission, meeting much more often than is specified in their charter.

The Committee's latest report touched on five areas:

1. Assessment of the 2009 State Auditor's Report and Management Letters

2. Benchmarking Analysis of Costs – Update

3. 2010 Five-Year Forecast – Review and Recommendation

4. Strategic Performance Objectives and Measures

5. Compensation Expense

Three times in their report, the Committee said that the past rate of operating expense growth in our school district is "not sustainable" going forward:

Page 2: In conclusion, while the Audit and Accountability Committee commends the District for reducing costs per student for 2009, the past expense growth rate significantly above CPI rates is not sustainable.

Page 3: The rate of growth in costs is simply not sustainable nor supported by current economic factors.

Page 5: As we indicated in our previous report and again in this report, the current rate of expense increases is unsustainable.

They closed their report with this statement:

In summary, compensation expense is the driving force of education costs in all districts. In HCSD compensation currently comprises over 87% of total District expenses. While it is important that the Administration continually watch all costs, compensation expense for Administrators, teachers and support staff is the only expenditure that "moves the needle". As the District works through the difficult economic circumstances and the strategic matters raised in this report, we recommend that all employees of the District participate in the development of solutions. Equitably sharing the duty of implementing solutions, financial and otherwise, will be important to community acceptance.

This is a wise and accurate summary, in my opinion. There is no single cause for the fiscal challenge in which we find ourselves, nor is there an easy solution. While it is indeed true that compensation costs make up most of the budget, and that our costs have been going up at a rate much greater than is typical in our current economy, there are other significant factors at play as well.

The most significant of those 'other factors' is the fiscal maelstrom in which the government of the State of Ohio finds itself. Ohio is not alone. The cover story of Time Magazine this week (Vol 175, No. 25) is titled "The Broken States of America." The writers examine the growing number of states that, if they were private sector industries, would be inclined to declare bankruptcy in order to shed the obligations accumulated from a generation-long spending spree. Those obligations cannot be met without implementing incredibly severe cuts in current and future spending, and raising taxes to a point that could choke off our fragile economy.

Because so much of the State's revenues come from personal and commercial income taxes, when the global economy took a dive, the revenues of the State of Ohio fell dramatically as well. Regardless of the pro-education promises Gov. Strickland made as a candidate, there just isn't enough money coming in for the State to honor all those expectations. The State must cover the ever-growing cost of Medicaid, as well as run the corrections system, which are also primary consumers of State funding. The result has been a manipulation of the public school funding formula such that districts perceived to be 'wealthy,' as is ours, have been left to fend on their own.

In plain English, that means that 100% of the incremental costs of running our school district are being fully borne by the property owners of our community – homeowners and businesses alike.

There are those who argue that the solution is obvious: radical reductions in the rate in which salaries and benefits are rising. The A & A Committee report says it clearly – only the compensation cost component of our budget is large enough such that a change in the rate of growth will make a real difference. I have certainly saying this for a very long time as well.

But we must acknowledge that there are other viewpoints. As one of the School Board's representatives to the A&A Committee, along with Dave Lundregan, I observed their discussions on this point, which are summarized in this statement on page 2:

"The District and community must remain cognizant, however, of the effect on the quality of education provided to students in taking any measures to reduce the growth in costs."

In other words, this isn't a dialog concerning only cost management. We are proud of what is accomplished in our schools, sometimes with national recognition, as was just recently the case with our being named one of 174 "Best Communities for Music Education" in the country. As we go about solving the fiscal problems that face us, few want that to come at the expense of the quality of our schools.

One of the key tactics Gov. Strickland has used to reduce expenditures at the State level has been to lay off one in twelve State workers, in addition to reductions in work hours and mandatory furloughs. This is hardly what one would expect from a Democratic governor, but like our schools district, it is just about the only real choice he has.

And so that brings us to the economics of our school district. As I have written here many times, there are only three knobs that we can turn to adjust our finances:

1. How much more do we want to increase our local property taxes?

As you can see from the following chart, we taxpayers have voted to raise our property taxes at a rate just over 7% per year - since 1975.

click to enlarge

However, as time has passed, the interval between levy requests has shortened. While through most of the 1970s and 1980s, levy requests were seven years apart, we have passed new Permanent Operating Levies in 2000 (4.3 mills effective), 2004 (8.1 mills effective), 2008 (6.9 mills effective) and will have another one on the ballot in 2011. The size is yet to be determined.

2. How much do we want to pay our teachers, staff and administrators?

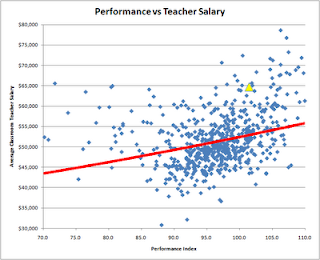

I have written much about teacher compensation – this article might be a good place to start. According to the CUPP Report generated by the Ohio Dept of Education, our classroom teachers in 2009 had an average salary of $64,703, which ranked 29th highest in the State among 614 districts.

Is that too much, too little, or about right? There will be no unanimity in the answer by any camp – neither teachers, staff, administrators nor the voters. Nonetheless, it will be negotiated this Fall, in secrecy, to a definite answer which will be expressed in new union contracts for teachers and staff, and individual employment contracts for administrators.

If you want to have any influence over this answer, you need to speak up now – right now – before negotiations commence. After negotiations end and the contracts are ratified by the unions, the only decision point remaining will be whether or not the School Board accepts the contracts.

3. To what degree will we accept cuts in programming, services, and staff?After the union contracts have been negotiated and signed, and the vote taken on next levy, the only knob remaining is how many people we employ.

As pointed out by the A&A Committee, the only class of expenditures we have that will 'move the needle' is personnel costs. There is simply no way of enacting millions of dollars in spending reductions without layoffs. And because the union contracts specify that employees are laid off starting with those with the least seniority – and therefore the lowest pay rates – it can require a large number of them to be laid off to reach a cost reduction target.

For example, my analysis suggests that to reduce spending by $1 million/yr, at least 30 employees would need to be laid off (15 FTE). To reduce spending by $10 million/yr would require on the order of 200 to be terminated.

At those levels, painful choices will have to be made. Which extracurricular programs and elective offerings will have to be eliminated? What services will be discontinued? How many more kids will we have in each classroom?

Reaching an acceptable balance of these three factors is quite frankly the most important task our community must undertake in the next few months.

In most ways, our schools define our community. The perceived quality of the schools is why we have chosen to live here, and is a significant factor in the preservation of our property values. Simultaneously, the compensation level we agree to for our school employees is the primary determinant of our property taxes, and every increase makes it harder for people to afford to live here.

I suspect that for things to work out, the school employees will have to accept less than they might like, and the voters will need to accept that they might need to pay more than is comfortable.

We can reach a reasonable agreement if the people of the community engage in the dialog, and the conversation remains respectful and empathetic.

Do you think we can do that without work stoppages, threats of strikes, name calling (on both sides), punitive program cut lists, and all those things which draw our children into the fray?

If it's really "all about the kids," let's show them how the people of one of the best school districts in the country figures out these tough problems. Wouldn't that be a wonderful gift to them – to show them how a community successfully deals with these situations, versus the 'scorched Earth' outcome we see in so many other places.

After all, we're going to leave them plenty of tough problems to solve when they grow up…