Does that mean that I am opposed to any new levy?

No. In fact, I voted in favor of the resolution to put a 6.9 mill Permanent Operating Levy on the May ballot, and voted YES on Issue #7 in this month's election.

As we all know, Issue #7 was defeated in an election in which fewer people bothered to vote than we have students in our school district. That doesn't mean the situation is resolved. We have, as a community, allowed the annual spending of our school district to grow well beyond our funding - a situation which is further exacerbated by significant cut backs in State funding. Barring unforeseen circumstances, I am confident that there will be a levy on the November ballot. The only questions are the size of the levy, and what gets cut if the levy issue fails.

Levy math is pretty simple. In our school district, we will raise about $2.2 million per year for each new mill of property tax. Last year, 1 mill would have raised $2.4 million/yr, but we are now operating on the assumption that the Franklin County Auditor will be reducing property valuations by about 8% in our community. This means that we now need about 1.09 mills to raise the same amount of money as 1 mill raised last year.

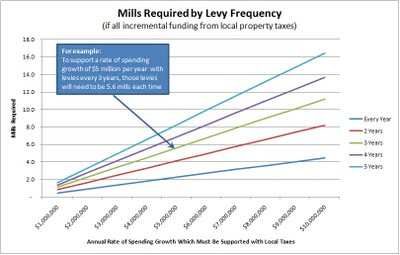

As I described in "Budget Knobs," another parameter we need to decide is how often we want to be asking for more money. To cover any particular rate of spending increase, the frequency in which new levies are enacted is inversely related to the size of the levy that will be needed. In plain English, the more often a levy is passed, the smaller it can be each time, given any particular rate of spending growth.

For visual folks like me, I thought a chart which shows this relationship might be helpful:

|

| click to enlarge |

The traditional approach is to determine all the new ways in which we're going to spend more money, then propose a levy of whatever size the Board thinks the public will tolerate, and then come back to the community again when that new level of funding is no longer enough.

How about if we go at this from the opposite direction?

What if we decide how often we are willing to let our property taxes increase, and by how much, and use that to determine the rate in which our spending can grow?

Isn't that more like the way we budget in our own households? After all, we don't make up a wish list of all the stuff we want, then go in to our boss' office and say "I've determined all the things I want to do and have, and you're going to have to commit to giving me a 10% raise every two years to support it!"

Don't we instead try to make some reasonably conservative projections of future income, and adjust our wants and desires to fit within that projected income stream?

Not everyone did of course, instead choosing to finance their unsustainable level of wants and desires by borrowing from credit cards and from the equity on their homes. The current economic situation in our country is caused largely by that behavior.

We've done a little of that in our school district as well. We didn't borrow money for daily operations - the law does not permit borrowing to fund current operations unless a school district has been declared to be in Fiscal Emergency by the State. But we did allow our spending to grow in excess of our revenue, in part by using one-time Federal stimulus money to fund current operations, and in part by emptying our rainy day fund.

Back to levies.

Now that we have this chart in our mind, is it as simple as saying "I'm willing to see my taxes go up by 5 mills every 3 years?" Unfortunately - no. There is also a structural reality we need to need to come to grips with: Compensation and benefits - which are approaching 90% of our spending - tend to rise exponentially, rather than linearly. This is what I mean:

Let's say a person is paid $10,000/yr, just to keep the math simple. Let's also say that the person has an employment contract specifying that the person will receive a 10% salary increase at the beginning of each year for three years. Since 10% of $10,000 is $1,000, that means the increase is $1,000 in the first year, making the new salary $11,000. What about year 2?

If the contract had specified that the person would receive a $1,000 raise each year, then the year 2 salary would be $12,000. But the contract said that the increase would be 10%. That means the raise would be $1,100 (10% of $11,000), and the new salary would be $12,100. The following year the salary would be $13,310. Graphically, it looks like this:

I wrote an article last July called "Teacher Salary History" which describes the compensation structure used in the current agreement with the teachers' union, the Hilliard Education Association. As I described, the two main components of that structure are the year to year base pay increases, and the step increases granted to teachers in years 0-15, 20 and 23 of their careers. Mathematically, this structure could be represented as follows:

Back to levies.

Now that we have this chart in our mind, is it as simple as saying "I'm willing to see my taxes go up by 5 mills every 3 years?" Unfortunately - no. There is also a structural reality we need to need to come to grips with: Compensation and benefits - which are approaching 90% of our spending - tend to rise exponentially, rather than linearly. This is what I mean:

Let's say a person is paid $10,000/yr, just to keep the math simple. Let's also say that the person has an employment contract specifying that the person will receive a 10% salary increase at the beginning of each year for three years. Since 10% of $10,000 is $1,000, that means the increase is $1,000 in the first year, making the new salary $11,000. What about year 2?

If the contract had specified that the person would receive a $1,000 raise each year, then the year 2 salary would be $12,000. But the contract said that the increase would be 10%. That means the raise would be $1,100 (10% of $11,000), and the new salary would be $12,100. The following year the salary would be $13,310. Graphically, it looks like this:

I wrote an article last July called "Teacher Salary History" which describes the compensation structure used in the current agreement with the teachers' union, the Hilliard Education Association. As I described, the two main components of that structure are the year to year base pay increases, and the step increases granted to teachers in years 0-15, 20 and 23 of their careers. Mathematically, this structure could be represented as follows:

f(n) = C((1+s)(1+b))n

Where:n = the number of years into the future for which pay is being calculated

C = the current salary for a teacher

s = the step increase factor, which is 4.15% in the current contract

b = the base pay increase factor, which was 3% for 2008-2010

So if our labor agreements cause compensation costs to rise exponentially, then it would seem that we need to come up with a revenue plan which grows exponentially as well.

As it turns out, this is exactly what we've been doing over the past 35 years. Except that it's not just the size of the levies which have been increasing, it's also been the frequency:

So what now - levies every two years? How long before we get to levies every year?

As it turns out, this is exactly what we've been doing over the past 35 years. Except that it's not just the size of the levies which have been increasing, it's also been the frequency:

|

| click to enlarge |

Maybe we need to think about a different approach altogether.

Many people believe the Ohio Supreme Court said property taxes are unconstitutional. That lawsuit - Derolph v. State of Ohio claimed that the State funding was insufficient, causing school districts with low property values to either tax themselves excessively, or have underfunded schools. In fact, in one of it's many opinions on this case, the Court noted that property taxes are the most stable means to fund schools.

Governments which are dependent on income taxes for revenue are hurting deeply these days, from local towns to the State of Ohio. Conversely, school districts which depend on property taxes - which is our case - have not taken any significant revenue hits in The Great Recession.

For many years, school leaders - especially those in affluent districts like ours - have complained that a law enacted in the 70s, commonly called "HB920" prevents property taxes from rising automatically with property values, and that this is the reason school districts had to keep coming back to the voters for more and more levies. As is often true with political statements, this one has some truth to it, but it's not the whole picture.

You see, HB920 also prevents property taxes from going down when real estate values tumble, as has happened in the past few years. So when you receive your new property value determination from the Franklin County Auditor later this summer, you'll probably see that the value of your home has been set about 8% lower than it was before. But that won't mean that your property taxes will decrease.

And it means the school district won't have to deal with a loss in local revenue.

And it means the school district won't have to deal with a loss in local revenue.

So here is our structural problem: The thing which drives our spending is compensation and benefits, and it rises exponentially. Our local revenue stream - upon which we will increasingly depend for additional funding - is very stable, but changes only upon passage of a new property tax levy. For our property tax revenue stream to grow exponentially, levy issues have to passed in exponentially larger sizes (not likely), and/or the frequency of levy issues has to increase exponentially (what's more frequent than every year?).

However, there is another tool available to us: Ohio law permits communities to impose school income taxes. Approximately 30% of all school districts in Ohio currently impose income taxes, collecting from a low of $3.01 per student in Zane Trace Local Schools (Ross County) to $3,091/student in Oberlin City Schools (Lorain County). For those districts with school income taxes, the average and median income tax collected per student is about $1,000.

It should be noted that districts with high school income tax rates, like Oberlin, tend to have much lower property tax rates. The high dependence on school income taxes would expose them to the same revenue risks as municipal government, although it should be noted that Oberlin is a community built around a college, which tends to make incomes more stable.

One more point deserving mention: Ohio law allows school districts to base income taxes on all income, just 'earned income' or a combination of both. The option of 'earned income' taxes came about to allow school districts to excuse those who have little or no earned income, notably senior citizens who tend to be living on pensions, retirements savings and Social Security (disclosure: I'm one of these people, so an earned income tax would be very beneficial to me). Politically, these levies tend to be much easier to pass, as senior citizens are much more likely to vote than the general population, and earned income taxes are an easy sell to them.

So is there a place for school income taxes in our school district?

PROS:

It should be noted that districts with high school income tax rates, like Oberlin, tend to have much lower property tax rates. The high dependence on school income taxes would expose them to the same revenue risks as municipal government, although it should be noted that Oberlin is a community built around a college, which tends to make incomes more stable.

One more point deserving mention: Ohio law allows school districts to base income taxes on all income, just 'earned income' or a combination of both. The option of 'earned income' taxes came about to allow school districts to excuse those who have little or no earned income, notably senior citizens who tend to be living on pensions, retirements savings and Social Security (disclosure: I'm one of these people, so an earned income tax would be very beneficial to me). Politically, these levies tend to be much easier to pass, as senior citizens are much more likely to vote than the general population, and earned income taxes are an easy sell to them.

So is there a place for school income taxes in our school district?

PROS:

- Since nearly all of our tax dollars are used to pay for the salaries and benefits of our district's employees, if we can negotiate labor agreements which are coupled to community income, a revenue stream derived from community income should automatically track funding needs, and significantly reduce if not eliminate the need for future property tax levies.

- Likewise, if our incomes go down, the amount of tax we have to pay diminishes as well. We can't be 'taxed out of our homes' in this case. But it means it is crucial that the labor agreements with the school employees have automatic adjustment clauses that reduce compensation commensurate with the revenue loss. Otherwise the loss of revenue will require layoffs to bring the spending back into alignment with the reduced revenue flow.

CONS:

- When our incomes go up, the amount of school taxes collected will increase correspondingly, without the need for a property tax levy vote (school leaders typically view this as a PRO).

- Without the need for a property tax levy vote, there will be a diminished need for the School Board and Administration to be accountable to the community. I personally like that we have that accountability today.

I'm beginning to think that a mixture of property tax levies and income taxes might be the best way to go. We would pass property tax levies of a reasonable size (e.g. 3 - 4 mills) every 5 years or so to provide a stable funding base. On top of that base, we would use income taxes to provide a revenue stream which changes with the state of the local economy.

The fiscal strategy we've been using for many years to operate our school districts just isn't going to work going forward. The compensation mechanism is no longer compatible with the funding realities. We need to look at new structures for both.

And we're running out of time to act.